Book Review: Woke Racism: How a New Religion Has Betrayed Black America by John McWhorter

“The new religion might be called ‘antiracism,’ but it features a racial essentialism…”

Woke Racism: How a New Religion Has Betrayed Black America by John McWhorter. Narrated by John McWhorter. Penguin Random House Audio, 2021. 5 hours (approx.).

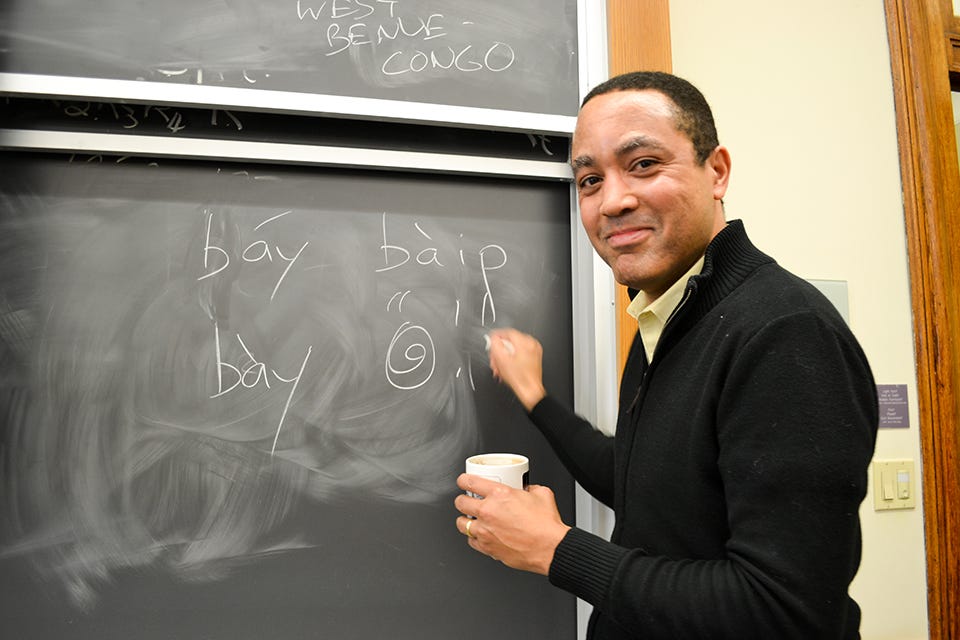

John McWhorter is an associate professor of linguistics at Columbia University. He is a prolific writer on linguistics and race relations in America. You can watch him on bloggingheads.tv with his “sparring partner” Glenn Loury. His latest book is Woke Racism: How a New Religion Has Betrayed Black America.

McWhorter clearly states the five “aims” of his book in the preface. Therefore, this reviewer needs only to determine whether he adequately accomplishes them. The answer is … almost.

To begin with, the five aims are:

“To argue that this new ideology is actually a religion in all but name, and that this explains why something so destructive and incoherent is so attractive to so many good people.”

“To explain why so many black people are attracted to a religion that treats us as simpletons.”

“To show that this religion is actively harmful to black people despite being intended as unprecedentedly anti-racist.”

“To show that a pragmatic, effective, liberal and even Democratic friendly agenda for rescuing black America need not be founded on the tenets of this new religion.”

“To suggest ways to lessen the grip of this new religion on our public culture.”

First Aim: this new ideology is actually a religion…

McWhorter replaces “woke” and “wokeism” with “elect” and “electism.” The later terms invoke images of medieval inquisitors. He justifies this in the following way:

The medieval Catholic passionately defended persecuting Jews and Muslims for reasons we now understand were rooted in lesser facets of being human. We spontaneously “other” those antique inquisitors in our times, but right here and now we’re faced with people who harbor the exact same brand of mission just against different persons. In 1500, it was about not being Christian. In 2020, it’s about not being sufficiently anti-racist with adherents supposing that this is a more intellectually and morally advance cause than antipathy to someone for being Catholic, Jewish or Muslim. They don’t see that they, too, are persecuting people for not adhering to their religion.

But is electism a religion? McWhorter begins by defining what is meant by religion. The word is commonly used to describe an ideology founded on a creation myth, guided by ancient texts and requiring certain beliefs beyond the reach of empirical experience. But, says McWhorter, “the word religion could easily apply as well to more recently emerged ways of thinking within which there is no explicit requirement to subscribe to unempirical beliefs, even if the school of thought does reveal itself to entail such beliefs upon analysis.”

One argument that he should have made here but did not is that religion need not be theistic. A Washington Free Beacon critic pointed this out: “Religions usually offer a theology, but wokeness has no account of God or gods plural.” But wokeness can still be a religion without a god.

In any case, McWhorter goes on to illustrate the similarities between religion and electism. The similarities include, but are not limited to:

Ritualistic behaviors. The white elect place their hands above their heads as an indication that they understand they bear white privilege. It indicates submission to a power “up there” looking down on them. Taking a knee after the George Floyd murder is a posture of prayer.

Clergy and preaching. Robin DiAngelo is a traveling celebrity preacher. Boston University’s Center for Anti-racist Research is a divinity school.

Holy texts. Ta-Nehisi Coates’ “The Case for Reparations” (The Atlantic, 2014) was neither the first nor the best argument for reparations, yet it was well received. It was a sermon prioritizing proclamation over information. New York Times reviewer A. O. Scott declared Coates’ Between the World and Me, “essential like water or air.”

Original Sin. “One is born marked by original sin in the same way to be white is to be born with the stain of unearned privilege,” explains McWhorter. One must embrace the teachings of Coates, DiAngelo and Ibram X. Kendi to be absolved from this sin.

All of this parallelism is interesting and, I suspect, true. But it does not prove McWhorter’s point. As the Free Beacon critic points out, “But lots of social movements throughout history have been motivated by ethical fervor and strong moral commitments—Prohibition, e.g., or the Satanic Panic of the 1980s—without being religious.”

Second Aim: why are people attracted to this religion…

Sigmund Freud wrote:

If you wish to expel religion from our European civilization you can only do it through another system of doctrines and from the outset this would take over all the psychological characteristics of religion, the same sanctity, rigidity and intolerance, the same prohibition of thought in self defense.

To put it more simply, a religious void will be filled by another religion. It is almost as if humans need religion, as “essential like water or air,” to use A. O. Scott’s words. Our society has become more secular; electism is filling the void. Related to this is a Durkheimian “collective effervescence” that white people achieve by having the correct ideas and virtue signaling them.

But of greater import is why black Americans settle for woke racism. McWhorter suggests it has to do with a damaged racial identity. Slavery, Jim Crow, red lining and no real sense of a mother country left black Americans grasping for who they are. The lack of an internally generated sense of legitimacy (or what makes one special) was filled by a survivor, or noble victim identity. Indeed, McWhorter describes a black teen at a Black Lives Matter protest in Settle happily declaring that blacks were holier than other races because of their victimhood. Black Americans settle for electism to feel whole.

He also suggests civil rights bills such as the fair housing act of 1968 robbed blacks of their pride: “Black people could not have a basic pride in having come the whole way despite and amid unreachable dismissal and pitiless overt roadblocks that we slowly but ultimately just pawed passed, over and beyond.”

Third Aim: this religion is actively harmful to black people…

This is McWhorter’s strongest point as he is able to provide concrete and measurable examples. Of these examples, the ones involving black boys and schools are the most startling. As we have seen in Dr. Warren Farrell’s The Boy Crisis, boys of any color are struggling. Woke racism is making it worse.

So-called anti-racists insist that black kids are expelled from schools more often because of discrimination: a white offender is a “scamp” while the black offender is a “thug.” But blacks do commit more violent offenses in schools. A study out of Philadelphia that McWhorter cites says, “Black kids were more than twice as likely to engage in violence at school than white kids.” Often the violence is black on black. “This means that if we follow these prophets’ advice and go easier on black boys we hinder the education of other black students.” This is preaching, not teaching. Religion numbs the anti-racists to the harm they cause.

Black and Latino students are being admitted to schools with significantly lower grades and test scores than those that would admit a white or Asian student. The 2003 Gratz vs. Bollinger court case involving the University of Michigan’s affirmative action program revealed that 20 out of the 100 points needed for admission were awarded on race alone. This leads to a “mismatching” of students to educational programs. The course work may be too hard or the teaching too fast. Many students in such circumstances will leave a major in frustration. A Duke University economist has shown this very “mismatching” has deterred a number of would-be black scientists.

McWhorter elsewhere says, anti-racists insists that:

It’s racist that black kids are underrepresented in New York City schools requiring high performance on a standardized test for admittance, and demands that we eliminate the test rather than direct black students to resources (many of them free) for practicing the test and reinstate gifted programs that shunted good numbers of black students into those very schools just a generation ago. That the result will be a lower quality of education in the schools and black students who are less prepared for exercising the mind muscle required by the test taking they will encounter later is considered beside the point.

Another harm caused by elect ideology is the infantilizing of blacks, particularly black scholars. Nikole Hannah-Jones insisted in the 1619 Project that the Revolutionary War was fought to preserve slavery. This has proven to be false, still she won a Pulitzer prize for it. “But our current cultural etiquette requires pretending that isn’t true because she’s black,” says McWhorter. “Someone has received a Pulitzer prize for mistaken interpretations of historical documents about which legions of actual scholars are expert. Meanwhile, the claim is being broadcast unquestioned in educational materials being distributed across the nation.” White people called her brave when they should have admonished her for her mistakes. This is bigotry of a kind.

Fourth Aim: rescuing black America need not be founded on the tenets of this new religion…

In 1987, a rich Philadelphian “adopted” 112 black kids. He guaranteed them paid education so long as they didn’t do drugs, didn’t commit crimes or didn’t have children before marriage. He also provided tutors, workshops, summer programs and counselors. Of the 112, 45 never finished high school. Out of the 67 boys, 19 became felons. Twelve years later, the 45 girls had 63 children between them, more than half before they turned 18 years old.

What held these kids back was culture.

This culture can be traced to racism. Past dehumanization led blacks to see themselves as separate from the norms of their surrounding society. For example, black students in the early days of desegregated schools experienced racism, both overt and covert. “That kind of rejection can make a person dis-identify from a whole environment, and one result was a sense that school was for white kids, something outside of the authentic black experience,” says McWhorter. While race relations would improve with time, the idea that school is for whites persists.

White leftists in the later 1960s encouraged poor black women to sign up for welfare payments they hadn’t previously felt they needed. They, the leftists, did this to collapse the economy and force a restart. In any case, this caused a shift in black culture - it became normal to be a single mother and/or collect government money instead of working.

Keeping this in mind, these are McWhorter’s three possible solutions:

End the War on Drugs. Without the illegal drug market many more black men will be forced to take legal jobs. They would have fewer encounters with the police, which, in turn, would mean fewer chances to be killed by a bad cop. Also, there would be less drug related violence. Finally, fathers would be able to parent their children rather than spending years in prison.

Teach Phonics. The whole-word method of reading does not work. School districts that switch to phonics raise the test scores of black kids.

Vocational Training. Not everyone needs to go to college. It is too expensive even for many middle-class Americans. A cheaper vocational school can open up just as many avenues for success.

It seems to me each of these solutions are an attempt to increase success in, and improve attitudes toward education, career and family units.

Fifth Aim: to lessen the grip of this new religion…

We can not get rid of woke racism any more than we can rid ourselves of Christianity or Islam. We must, says McWhorter, find ways to deal with them. One simple method is to simply say, “no.” Do not engage. Do not participate in their ideology. The elect will call you a racist; that is unavoidable. Tell the elect you disagree and move on. I don’t think McWhorter appreciates the devastation such an accusation can have on a white person, however. One often can not move on.

Conclusion

Ultimately, John McWhorter’s Woke Racism falls short. While I believe he is correct in that wokeism is a religion, it’s not what I believe but what McWhorter can prove that counts. Listing the parallels with religion is a good start, but he needed to provide evidence more solid than that.

McWhorter’s strongest section is the harm caused by elect ideology. As I have stated, his evidence is concrete and measurable. If he fails to convince the reader that woke is a religion, perhaps convincing them that woke is harmful will be enough.