Psycho (1960)

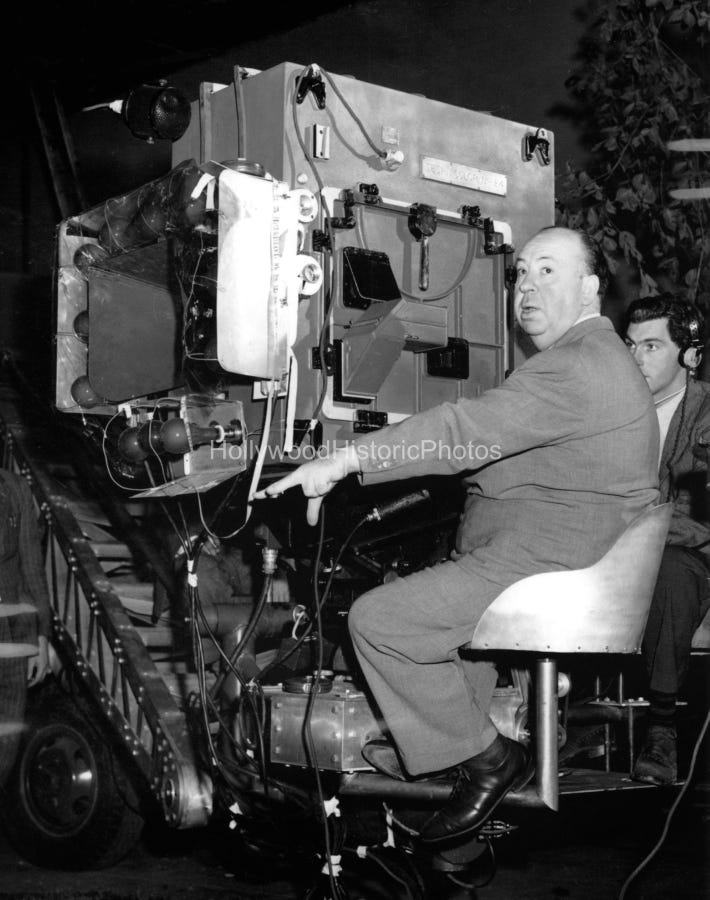

According to his daughter, Patty, Hitchcock wanted to film Psycho cheaply and quickly using the television crew that produced Alfred Hitchcock Presents. They shot the movie in less than three months at a cost of $807,000.

Composer Bernard Hermann used only stringed instruments for the score. Paul Hirsch, an editor who worked with Hermann, said he composed music to match the content of the film. In the case of Psycho that meant “a black and white score … because he wanted to reflect the black and white, stark quality of the picture.” The decision to make the film black and white was to hide the gore, according to Patty.

The story makes use of the false protagonist device. Initially, Psycho is about Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) who steals a sum of money and goes on the run. But she is murdered about halfway through the narrative. Fearing late comers would miss Janet Leigh, Hitchcock had theaters admit no one after the start of the movie.

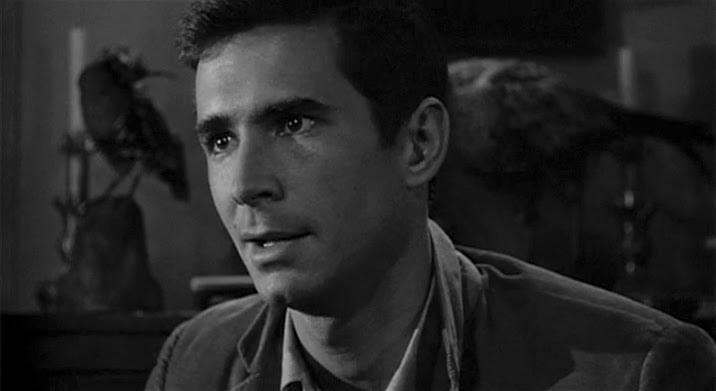

The focus shifts to Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins). Ostensibly, Norman covers up the murder committed by his jealous mother. However, the truth is later revealed when sister Lila (Vera Miles) and boyfriend Sam (John Gavin) search for the missing Marion.

For the opening Hitchcock originally wanted a helicopter shot with Phoenix, Arizona in the “far” background, according to assistant director Hilton A. Green. The titles would run as the camera slowly moved closer and closer and finally into the hotel window. However, the helicopter was too “bumpy” and “jerky,” so Hitch settled for a series of wide pans.

Going through a window is typical Hitchcock. It not only sets the location for the scene but also establishes the audience as a voyeur - a “Tom” peeping into the lives of the characters. This is particularly true for Psycho: once inside the hotel room we see Marion and Sam getting dressed after a premarital affair. They are meeting in secret because Sam’s financial situation forbids them from marrying. Note, also, that Marion is wearing white.

Later, she is wearing black. The money she was entrusted with sits upon her bed. The camera zooms in on it and then pans to a packed suitcase. We understand she means to steal it. The change in wardrobe color indicates Marion’s change in moral character. Desperate to marry Sam, she rashly takes the cash and heads to his home in Fairvale, California.

The trip to California is kept suspenseful in different ways. Namely, Marion repeatedly almost gets caught. A police officer tails her to a used car lot. She gives the cop a furtive glance, but the salesman (John Anderson) catches it. Now both men suspect her … of something but they don’t know what. Marion is not a good thief.

A storm makes driving unsafe, so she spends the night at the Bates Motel. Norman initially reaches for cabin key number three. However, he stops to consider key two before settling on key one. The over the shoulder shot of his hand directs the audience to this small act. It’s the audience’s first hint that something is not right despite him stating that cabin one is closer if she needs anything. Indeed, Norman is able to peep on Marion as she undresses in that cabin.

Before that, however, there is an important conversation between the two characters. It takes place in the parlor behind the motel office. The room is decorated with a number of stuffed birds.

The dialogue starts at medium shot, but as the conversation turns to mother (and becomes more sinister) the camera moves closer until there is a tight shot on Norman’s face made even more extreme when he leans into the camera. This puts emphasis on the topic of madness with regard to Mrs. Bates and her possible institutionalization. Perkins’s performance here is chilling.

Also, the shots are framed to include the stuffed birds. This foreshadows the final revelation that Mrs. Bates is dead, her body preserved by Norman’s skill as a taxidermist. When the subject of his mother first comes up the shot of Norman temporarily changes from straight on to a side shot at a low angle. This puts a threatening raptor into the frame. It leers suggestively over Norman. There could be some symbolism here, too: “stuffing the bird” is slang for sex, suggesting the inappropriate nature of this mother/son relationship.

This brings us to the infamous shower scene. The montage sequence took seven days to shoot. It had 78 different setups and 52 cuts. The final on screen run time is about 20 seconds. Hitchcock discusses it in this interview.

It begins with the camera in the shower looking out. The curtain obscures our view, yet we see the door open, and a female figure walk in. The camera zooms in, removing Marion from the frame but centering the shadow, ostensibly Mrs. Bates. She pulls back the curtain. The knife is raised. Marion screams. The montage begins.

The rapid succession of images is that of the knife being raised and lowered and parts of Marion's body as she writhes and struggles. At no point do we see the knife enter her body. It’s all suggested by the rapid editing. As Janet Leigh pointed out, each cut of the film becomes a cut of the knife in the mind of the viewer.

The sequence ends by following the blood down the drain. That image dissolves to Marion’s eye suggesting her life has drained away. The camera then pans across the room to where she had hidden the money indicating this was a crime of passion, not profit.

Sam and Lila look for Marion with the aid of private detective Arbogast (Martin Balsam). Arbogast enters the Bates’ home intending to interview the mother. Here, Hitchcock uses orchestration to create shock as he explains in the above mentioned interview.

The scene starts at a waist shot as Arbogast mounts the stairs. Then Hitch moves the camera to the ceiling to make the characters small (this also helps hide the true identity of Mrs. Bates). Finally, he cuts to a closeup - “a big head” - of the victim as he receives a knife blow. “This is size of image put together to create shock,” Hitchcock said.

With both Marion and Arbogast missing and the local police useless, Lila and Sam take matters into their own hands. Sam distracts Norman while Lila snoops around the house in search of the mother. Later, when Norman comes looking for her, Lila hides in the stairwell. There is a single shot with both characters in frame, the one unware of the other. Lila then enters the fruit cellar.

There is a woman sitting with her back toward the door. Marion walks over, the camera dollies with her. Hitchcock purposely includes the dangling light bulb in this shot. It even flares when Lila at last meets mother.

The chair spins around to reveal the woman’s features. She’s a corpse. Lila screams. Her flailing hand smacks the light bulb, sending it swinging. The fruit cellar is cast in chaotically swaying shadows as Norman in drag enters the room with a large knife. Sam subdues him. The struggle is choreographed so that the wig falls off and the dress is torn - in case there was any doubt about his identity.

There are brilliant crosscuts here, too. Lila’s reaction to Norman’s entrance for one. The face of mother in alternating light and shadow for another.

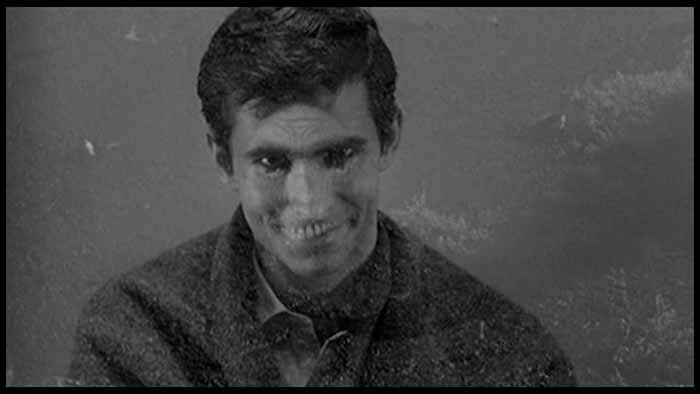

The penultimate image is Norman in the police station with his mother’s skull superimposed over his face. Mrs. Bates has taken complete control.

Rope (1948)

Rope is based on a one-set play by Patrick Hamilton. Hitchcock wanted to “make the stage play mobile,” by which he meant to make a movie like a play, that is, as one long shot of continuous action. However, that wasn’t possible. The cameras of the time could only shoot for 10 minutes before the film had to be changed, requiring a cut.

Hitchcock attempted to hide these mandatory cuts by (usually) panning into a character’s back so as to completely obscure the screen. The cut is then made. The fresh film begins by panning out of that character’s back. However, as the screenwriter for Rope, Arthur Laurents, points out in the documentary Rope Unleashed, this method revealed what Hitchcock had hoped to hide.

Moreover, these “hidden” cuts are clunky to say the least. They pull the audience out of the action. They create continuity errors (blood on a hand that wasn’t there before, or perfectly combed hair now disheveled). The panning in and out of backsides is visually jarring and baffling without the greater context as outlined above.

Still, I include Rope in my study of visual storytelling because there is a lot that works very well in this movie. Also, the shooting method was ambitious if not successful.

The technicolor cameras were huge. They also had to move about the set between 25 and 30 times in each 10-minute take. To accommodate their size and movement the walls of the set were built on casters. Hitchcock said, “Whole walls of the apartment had to slide away to allow the camera to follow the actors through narrow doors.”

The furniture also had to be moved and then replaced in its exact original spot. About this actor Farley Granger said, “One of my biggest problems was having to trust that when I sat down, there would be a chair under my rear end, that the stagehand had gotten it there in time.”

It took a team of prop, camera and sound men to keep everything moving. Cast and crew had to be precisely choreographed. The movements were written out on a blackboard and reviewed at length. The floor was marked accordingly. Each 10-minute take was rehearsed for an entire day before shooting on the next. And while all that is happening the actors still delivered their lines and gave expert performances.

Brandon Shaw and Phillip Morgan (John Dall and Farley Granger, respectively) strangle their “useless” classmate, David Kently (Dick Hogan), with a length of rope. The exploration of their motives is the thematic heart of the movie.

Guided by the philosophical musings of their former prep-school housemaster, Rupert Cadell, the Harvard educated boys believe murder can and should be legal for the privileged few. Murder is an art, they believe; a thing of transcendental beauty. Committing the perfect murder is the pinnacle of aesthetic achievement. For Brandon, the finishing touch is throwing a party for David's friends and family while the body is in the chest from which he serves them dinner.

Rupert is one of the guests. He is played by the inimitable Jimmy Stewart. He becomes suspicious of the boys and, like a detective, pieces together what happened. In the climax, Rupert confronts the boys but, more importantly, confronts his own demons. It was his philosophy built on the work of Nietzsche’s “superman” that he imparted to the boys and, thus, inspired them to murder; or, as Rupert himself puts it, “... you’ve given my words a meaning that I never dreamed of!”

Indeed, words have no meaning without action, and that is precisely what motivated Brandon and Phillip.

The opening shot is a closeup on David's agonizing face. We also see the rope around his neck and the gloved hands tightening it. The camera pulls out to reveal the murderers. This is a reversal of Hitchcock’s typical use of closeups. The emphasized (closeup) shot comes first rather than second. Notably, it is Phillip who holds the rope.

There is a sizable chunk of dialogue before the housekeeper, Mrs. Wilson (Edith Evanson), arrives. Most of the watching, which gives subtext to the dialogue, is in the reactions of the two boys. Brandon is excited. Phillip is visibly perturbed. At one point Phillip asks Brandon how he felt “during it.” Unable to answer, Brandon changes the subject even as the camera changes its subject by panning to the dining room table. It is set for a party. Brandon explains the party is like the artist’s signature on the painting.

He also gets the idea of serving dinner from the chest in which David’s body is hidden. As they prepare it, Hitchcock frames the shot to reveal the murder weapon dangling from the chest. The audience momentarily believes they’ll miss it, and that’ll give up the jig. But it’s a red herring. Phillip catches the mistake. The interaction that follows gives us insight into their characters. Phillip is a neurotic wreck. He refuses to even touch the rope. Brandon, on the other hand, pulls it out and, later, nonchalantly twirls it around in full view of Mrs. Wilson.

The rope twirling scene is brilliant because it lets the audience know exactly what will happen: Brandon’s arrogance will undo him. The suspense is not knowing exactly how or when. The fun is knowing what he doesn’t.

Mrs. Atwater (Constance Collier) is David’s aunt. She comes to the party in place of his mother who is sick. She mistakes another guest for David and cries out his name. We hear a crack. The camera does a long pan and zooms in on Phillip’s hand. The shock of hearing David’s name called out caused him to crush the glass he held. This is an example of how Hitchcock communicates inner thoughts or feelings without having a character explicitly state them.

Coincidently, there is another scene involving Phillip’s hands and Mrs. Atwater. The latter reads palms and declares Phillip’s hands will bring him great fame. She is referring to his piano playing, of course. But Phillip takes her meaning differently. He turns away from her, his hands paralyzed in a rigid half-grip. At this point I probably don’t need to say what Hitchcock is doing with his camera, but the closeup on the hands pans up to show Phillip’s terrified face.

After dinner, Mrs. Wilson clears the chest. Meanwhile, the other guests discuss David's conspicuous absence. The conversation isn’t important, and so Hitch has it take place off camera. What is important is Mrs. Wilson now opening the chest to put away some books. Will she find the body? No, Brandon stops her. This is a superb example of bomb theory.

Rupert suspects something is amiss when he notices the expensive champagne. Brandon has his reasons for it, but Rupert is unconvinced. Of course, the audience knows the champagne is to celebrate the murder.

Rupert also overhears a number of telling conversations. Each time he can be seen over another character’s shoulder, distant and out of focus but obvious. He then steps into focus as he injects himself into the conversation and fishes for more information.

There are three moments that clinch Rupert’s suspicions.

In the first, Brandon tells the story of Phillip strangling chickens at the Shaw’s farm. The latter cries out, “That’s a lie!” There is an unmasked cut (one of a few) to a closeup of Rupert. He is reacting to Phillip’s outburst. Later, Rupert reveals he was there at the farm and Phillip was “quite the good chicken strangler as I recall.”

In the second, Rupert is grilling Phillip about his lies and the machinations of Brandon. David’s father, Henry (Sir Cedrick Hardwicke), walks into frame. Or, more accurately, the books that he carries enter the frame. They are tied together with the murder weapon. In the frame, also, is Phillip’s reaction.

In the third, Mrs. Wilson accidentally hands Rupert the wrong hat. Taking it off, he catches the monograph inside: D. K.

Rupert leaves with the correct hat but invents an excuse to come back. After some talk, he outlines what he believes the boys did to David. As Rupert does this, the camera moves around the apartment focusing on the places and things relevant to his monologue. For example, when Rupert says they probably welcomed David at the door and then offered him a drink, the camera pans from the entry hall to the drink tray.

The audience believes Rupert’s theory will continue to the chest, and so will the camera. But it’s another red herring. Both stop. Rupert doesn’t know what they did with the body. It’s not clear to me if he truly doesn’t know or if this is a tactic. I suspect the latter because throughout the movie Rupert exhibits investigatory prowess.

In any case, Rupert produces the rope. He got it off the books in Henry’s possession. He also teases how exciting and suspenseful it would be to accompany the boys to Connecticut. Phillip cries, “He’s got it. He’s got it! He knows!”

Phillip grabs a gun. Rupert wrestles it from him. He then looks inside the chest. Its contents are not shown, but we know what he sees. Brandon tries to explain using Rupert’s own theories against him. The camera turns on the boys’ former mentor as he realizes his own culpability.

He sits in a chair, feeling faint perhaps. The camera angles down on him with Brandon standing up almost out of frame. He accepts as much guilt that belongs to him but also rightly points out Brandon’s immorality and arrogance. At this point he stands up, the camera moves with him and the two become philosophical combatants. Rupert speech follows:

Brandon. Brandon, till this very moment, this world and the people in it have always been dark and incomprehensible to me. I’ve tried to clear my way with logic and superior intellect. And you’ve thrown my own words right back in my face, Brandon. You were right, too. If nothing else, a man should stand by his words. But you’ve given my words a meaning that I never dreamed of! And you’ve tried to twist them into a cold, logical excuse for your ugly murder! Well, they never were that Brandon, and you can't make them that. There must have been something deep inside you from the very start that let you do this thing, but there’s always been something deep inside me, that would never let me do it - and would never let me be a party to it now.

Brandon asks, “What do you mean?” Rupert circles around the younger man. So does the camera. We see his fallen face in full. Then Rupert paces and the camera follows him, positioning the back of Brandon alternatively on the right and left of the frame. Rupert continues:

I mean that tonight you’ve made me ashamed of every concept I ever had of superior or inferior beings. But I thank you for that shame, because now I know that we are each of us a separate human being, Brandon. With the right to live and work and think as individuals, but with an obligation to the society we live in. By what right do you dare to say that there's a superior few to which you belong? By what right did you decide that that boy in there was inferior and could be killed? Did you think you were God, Brandon? Is that what you thought when you choked the life out of him? Is that what you thought when you served food from his grave?! I don't know who you are, but I know what you've done. You've murdered! You choked the life out of a fellow human being who could live and love as you never could, and never will again!

The camera finally comes to rest with all three characters in frame. Brandon asks, “What are you doing?” Rupert replies:

It's not what I'm going to do, Brandon. It's what society is going to do. I don't know what that will be, but I can guess, and I can help. You're going to die, Brandon. Both of you. You are going to die.

The camera closes in on Rupert as he moves to the window and opens it. There is a medium closeup of his arm holding the revolver. He discharges three rounds into the air - an S.O.S. The camera backs out of the medium closeup of the arm to show the entire room and the three characters in a long shot. The final image suggests exhaustion and relief.

Rear Window (1954)

Rear Window is my favorite Hitchcock movie. I am in good company; it was Jimmy Stewart’s favorite, too. More than this, it captures everything that Hitchcock’s cinema stood for. As filmmaker Curtis Hanson said, “If one were to ask, ‘What are the movies of Alfred Hitchcock like?’ Somebody that knew nothing about movies. You could show them Rear Window and in a sense, touch on everything in Hitchcock.”

This film is another one of Hitchcock’s “limited setting” or one room dramas. Others include Lifeboat, Dial M for Murder and Rope. The setting is a courtyard to which a number of apartment complexes back.

Paramount Pictures didn’t have a soundstage tall enough to accommodate the buildings that Hitchcock and his art director, Mac Johnson, wanted to create. They brought the problem to production designer Henry Bumstead, who knew the soundstages had basement storage space. He suggested they cut out the floor. Johnson asked, “They wouldn’t let me do that, would they?” To which Bumstead replied, “I bet they will for Hitchcock.” And they did.

The first floor and lawns were, therefore, in the basement of the soundstage. Stewart’s second story apartment was actually on the ground floor. The upper most rooms were practically in the studio's lighting grid.

Each apartment “worked,” meaning they were practically livable domiciles. Certainly they were furnished. One character pours a glass of water from the sink, suggesting they had plumbing. The actors in these apartments wore earpieces so Hitch could direct them in real time as he filmed.

Rear Window stars future princess Grace Kelly as Lisa Fremont and the legendary James Stewart as L. B. Jefferys. It is, at its heart, a love story - with a murderous twist.

Jefferys, or Jeff, is a globe-trotting photographer. An accident leaves him bound to a wheelchair with a broken leg. With nothing better to do, he watches his neighbors for entertainment. It’s all fun and games until he suspects Lars Thorwald (Raymond Burr) of murdering his wife.

Meanwhile, his relationship with Lisa is on the rocks. He believes they are incompatible. She “belongs to that rarefied atmosphere of Park Avenue, you know. Expensive restaurants, literary cocktail parties …” While Jefferys is “... a camera bum who never has more than a week's salary in the bank.” But she proves this fashionista has an adventurous side when she enters Thorwald’s apartment to capture hard evidence of his crime.

The entirety of Rear Window is an exercise in the Kuleshov effect, or subjective point of view. As filmmaker Peter Bogdanovich describes it:

You have a shot of Jimmy Stewart, you show what he's looking at, you see his reaction. The entire movie is based on that. He looks, you see what he sees, he reacts. That is kind of the heart of Hitchcock's film making. He has the incredible ability to put you in the point of view of the leading character or whatever character. And he does it with considerable dexterity.

The movie opens with the camera coming out of Jeff’s apartment window. This is an inversion of Hitchcock’s typical opening where the camera moves into the room. In either case the shot establishes the setting. The audience is still a voyeur, it’s just that this time we look into other people’s lives from within our own. It also sets up the premise of the film as well as its method of presentation: spying out a window. Moreover, it puts the audience in the room with the main character.

The setting is further established as the camera pans around the courtyard. It comes back to a sleeping man who is sweating. It must be hot. Cut to thermostat. Indeed, it’s nearly 100F.

The other players are now introduced. First we see the musician who has a piano. Then the older couple who sleep on the fire escape to stay cool. Next is Miss Torso (Georgine Darcy), a sexy blonde who prances around in her underwear.

We end where we began - the sweaty man. The camera pans to his legs. One is in a cast. The writing on it reads: “Here lies the broken bones of L. B. Jefferys.” A neat trick! With out a word spoken we learn our protagonist’s name.

The camera moves out to show he’s wheelchair bound. It next pans to a series of objects in his room that visually tells Jefferys’ back story:

He’s been in a race track accident (broken leg; smashed camera; crashing car picture).

He is an adventurous photographer (framed pictures; camera collection).

He has a relationship with a fashion model (framed negative that matches the cover of a fashion magazine).

In the next scene Jefferys is talking with his editor. Much of the dialogue just reaffirms what we already learned visually. What’s important is the watching. He sees the lives of various couples in various stages of their relationships. Each of these examples shape Jeff’s own view of marriage, which becomes the central question for him: to marry or not to marry Lisa.

In particular, the Thorwalds bicker and look unhappy. While watching them Jeff effectively says he’d never tolerate a nagging wife. The editor replies, “Jeff, wives don’t nag, they discuss.” To which Jeff quips, “… in my neighborhood they still nag.”

That night, Lisa comes over. Grace Kelly’s introduction in Rear Window is one of the most beautifully shot images with one of the most beautiful actresses.

She’s prepared a special diner for him in celebration of his last week in the cast. But the lovely evening turns into a big fight. The relationship might be over.

Later, Jefferys wakes up in the middle of the night. A woman screams, “Don’t” and there’s a crash. He sees Lars Thorwald take a large suitcase out into the rain. It’s about 2 a.m. according to his watch, shown in extreme closeup. The image fades and reappears. Now the watch says 2:35. Thorwald returns, then leaves a second time. These soggy, night time trips indicate something is not right.

However, Hitchcock plays a trick on his audience. He breaks from Jefferys’ POV, who is sleeping, so we can see Thorwald leaving his home with a woman. Who could she be but his wife? This plants the seed of doubt. Although Jefferys is convinced the wife is dead, the audience isn’t so sure.

This doubt is reaffirmed in the first Lt. Doyle (Wendell Corey) scene. Jeff asked the NYPD detective and personal friend to look into this possible homicide. Doyle is skeptical. So is the audience. For this scene our sympathy is shifted to Doyle as the camera shifts to follow him around, focuses on him, puts him at the center of attention. However, in subsequent scenes Doyle comes off as foolish. In one case he spills a drink on himself.

A dog that earlier dug up Thorwald’s flowers is found dead. Hitch shows the neighbors' reactions to the death. This is the first of only two times Hitchcock films outside of Jefferys’ apartment (the other being the climax). This moment also cements Thorwald’s guilt: he is the only one not to come to the window.

More certain now than ever before, Jefferys writes a threatening letter to pressure Thorwald. The camera shoots from the ceiling and zooms in on the note. The dramatic angle shows what is written, but it also emphasizes the character development: no longer content to watch, our heroes take action.

Lisa delivers the letter. She is almost caught, but the scrappy socialite gets away. Mostly Jeff has been in medium shots throughout the film. Now, when Lisa returns from her errand panting with excitement, Hitchcock puts him in closeup. We see how proud he is of her. Again, the camera emphasizes the character development taking place here. Jefferys now realizes Lisa is the woman he wants.

But they still need hard evidence. Lisa takes the initiative and digs up the flowerbed that the dead dog had been snooping around. Nothing. She then climbs the fire escape and through the window - in high heels, no less! - to Thorwald’s room.

As she searches, we see Lars Thorwald return home.

Jefferys was distracted with Miss Lonelyhearts so he was unable to give Lisa the warning signal. He instead calls the police. In the meantime, Thorwald discovers Lisa in the bedroom. He attacks her. This crosscuts to Jeffery’s reactions: panic and nearly in tears. There is even a low angle shot that somehow heightens the fear.

The police arrive just in time. They arrest Lisa, but she leaves with Mrs. Thorwald’s wedding ring. She signals this to Jeff. Lars, however, notices the signal. He lifts his eyes to meet the camera. He looks straight into the audience. We’ve been caught!

Thorwald confronts Jeff inside the latter’s room. Part of this scene is filmed from killer’s point of view. Jefferys is a silent figure shrouded in darkness, shown in a long shot. The killer pleads, “What do you want from me?” For a moment we are in his shoes. We sympathize with him. What did Jefferys want? Justice, I suppose but I almost believe he was just being mean.

Thorwald wrestles with Jeff. The scene is a montage much like the final struggle in Shadow of a Doubt. About this scene Hitchcock said in an interview:

I just photographed that with feet, legs, arms, heads. Completely montage. I also photographed it from a distance. There was no comparison between the two. There never is, you know? Bar room fights or whatever they do in Westerns … they're always shot at a distance. But it's much more effective if it's done in montage, because you involve the audience much more. That's the secret of that type of montage in films.

Jeff falls out the window but survives. Lt. Doyle arrives to arrest Thorwald. The final image is Jefferys in his wheelchair with two broken legs and Lisa reading Beyond the High Himalayas. However, she notices Jefferys is sleeping and picks up Bazaar magazine.

Besides the main story there are smaller stories with the neighbors. These are told almost entirely visually and are interwoven into the main plot. For example, while Thorwald is busy behind closed windows Hitchcock cuts to the composer coming home drunk. Obviously he is struggling with his work and took to self medication.

The best example of this is Miss Lonelyhearts (Judith Evelyn). We watch her go on a pretend date. She mimes every aspect of it from answering the door to pouring a drink to receiving a kiss on the cheek. When she does bring a date home it goes badly: she pushes him away and slaps him.

Near the climax, Lonelyhearts empties a large bottle of red pills. She fills a glass full of water. Next, she grabs her bible and sits down to write. Obviously it is a suicide note. She means to swallow all those pills. But the composer’s music - now complete - stops her. It is Miss Lonelyhearts who distracted Jefferys when he should have been signaling Lisa of Thorwald’s return.

Afterword

Thanks for participating in this year’s virtual film study class. I poured my heart and soul into these essays. It was a lot of work. I hoped you enjoyed them and learned something about how movies are made.

Once again, if you feel I left something out feel free to contact me by leaving a comment below. I did my best to link all my research. Most information came from DVD bonus materials.