Theme as Question: What A Clockwork Orange Taught Me About Writing

Too often, theme is mistaken for plot. Burgess shows us how to ask better questions - and let the story do the answering.

As a student, I was taught that theme is “what a novel is about.” That definition never sat right with me. If asked, “What is the theme of A Clockwork Orange?” one could reasonably answer, “It’s about teenage violence,” because, as the plot summary shows, it is about a gang of kids terrorizing London. Nevertheless, that is not the theme. So, I don’t believe that definition is a good one. Theme is better defined as the question the novel attempts to answer. I say "attempts" because sometimes there are no answers - or no good ones, anyway.

An author asks a question and explores it through the actions and choices of his characters. As the project unfolds, he may come closer to an answer - maybe even arrive at one. This is what differentiates the novel (i.e., art) from propaganda, which starts with an answer and reverse engineers the story to fit it.

A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess is a superb example of theme as question. In it, a teenage delinquent named Alex leads a gang of “droogs” in a not-too-distant future. Their idea of a good time is assault, theft and rape. After being arrested, Alex undergoes an experimental state-sponsored treatment that effectively brainwashes him, stripping him of free will. He’s later “cured” and goes back to his old ways, but eventually, Alex begins to tire of ultraviolence and dreams of a different life, including fatherhood.

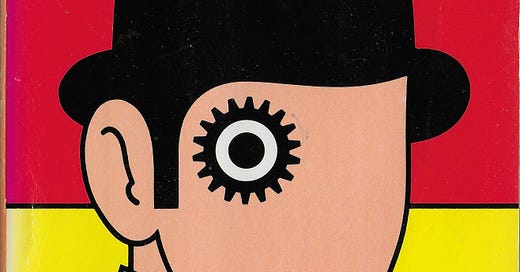

The question Burgess poses is: What makes a person good and is goodness still goodness if it’s not freely chosen? There is evil in the world because humans choose to do evil. Alex states this explicitly: “I do what I do because I like to do.” His behavior is not the result of external influences - necessity, trauma, poverty and so on. Rather, it is a deliberate, uncoerced choice. And that’s what makes free will so terrifying. Still, it is a necessary part of being human. Without it, humans are like a clockwork orange: something that appears alive, juicy and nutritious, but is in fact cold, mechanical and dead - and that’s precisely the point of the title.

When the state intervenes through the Ludovico Technique, they don’t make Alex good - they make him incapable of evil. That’s a nuanced but crucial difference. A person is not (necessarily) virtuous because he cannot, and therefore does not, commit evil. Rather, he is virtuous when he can do evil but chooses not to. Choice is paramount in morality.

In the 21st chapter - which was excluded from early American editions and, consequently, from the Kubrick film - we see Alex maturing out of delinquency. His transformation doesn’t come from revelation or remorse, but from fatigue. He simply grows out of violence. This means Alex could have changed the whole damn time - not by force or conditioning, but through time, boredom and the natural wearing-down of youth’s madness. The State never needed to step in. Growth was coming anyway.

This idea cuts hard against the Kubrick film’s nihilism. The film ends with Alex reverting to his old self, implying that true change is impossible. Burgess, on the other hand, believed in maturation - in the slow erosion of cruelty. His message isn’t that people are irredeemable; it’s that they must be allowed to redeem themselves.

Alex’s final lines aren’t full of repentance: “I was growing up, O my brothers. Yes, growing up.” He doesn’t apologize for his past. But he dreams of a son, of passing on his love of music, of protecting innocence, of something better. It’s not a happy ending, but it is a real one - messy, flawed and full of the uneasy hope that maybe, just maybe, we can grow out of our worst selves.

In conclusion, A Clockwork Orange illustrates theme as question. Burgess doesn't hand us a clean answer to “What makes a person good?” but forces us to wrestle with the nature of morality, free will and the danger of state-imposed virtue. That’s what makes the novel art rather than ideology: it doesn’t preach; it inquires. And as readers, we are left not with a thesis, but with a provocation - one that still matters in this age that tries to solve moral problems with machinery.

I wrote the rough draft of this essay and used feedback from ChatGPT to improve it. Most of the suggestions were good. Some were crap. I’m experimenting with this crazy new technology as an editing tool - kind of like spell check back in the early 2000s. I felt obliged to include this note because transparency matters here at IGReviews. Thanks for reading.